A Lexington County charter school is expanding into a neighboring school district.

Gray Collegiate Academy announced Thursday that it will open a branch campus next fall in the Irmo area, adding students and staff on top of its current operations at its West Columbia campus.

“We’ve outgrown our capacity at our West Columbia campus,” said Gray Principal Brian Newsome. He added that the school researched opportunities to expand to other areas of South Carolina, which became a reality last summer.

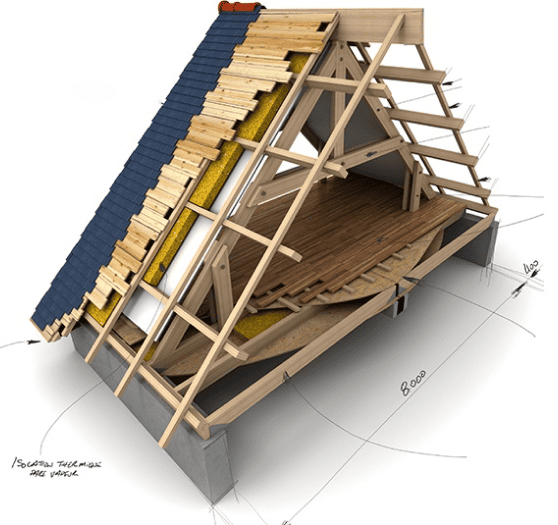

The new campus will be located at Koon Road and Broad River Road, Newsome said at a press conference at Gray’s existing campus. The school will begin operations in the fall with three modular buildings with eight classroom each, plus a smaller module for an office. The plan is to open with a class of around 600 students in grades six to 10, with the goal of eventually attracting 1,000 pupils to a full six-to-12 grade school with modern facilities, including a multi-purpose outdoor cafeteria and physical education space, with help from Performance Charter School Development.

Since it started in 2017, Gray has become known for its athletic success, winning multiple state titles in different sports.

The current Gray campus is located in the Lexington 2 school district, but as a charter school it operates independently of the local school board and can attract students from a broader area. Gray is one of two dozen schools in the state sponsored by the Charter Institute at Erskine, an offshoot of Erskine College.

The new campus will be roughly in between two high schools in the Lexington-Richland 5 school district, four miles from Dutch Fork and six miles from Irmo High. Newsome said the new location will be more convenient for some students who already live closer to the Irmo area than Gray’s current campus, but the school conducted surveys to establish a demand for charter services in the area as well. The new school will have a staff of 26, 13 of whom are expected to move over from the current Gray campus and then be replaced in West Columbia.

Asked about the new charter school in the district, Lexington-Richland 5 responded with a statement that did not directly mention Gray.

“School District Five of Lexington & Richland Counties recognizes the importance of choice in education,” the statement said. “Our community offers charter, private, homeschool, and magnet programs to ensure every family has a great choice for the education of their child.”

Newsome said Gray is continuing to look at other locations as well with plans for further expansion, both within and outside South Carolina.

“The opportunity came to purchase this site and move in quickly over the summer,” Newsome said of the 42-acre Koon Road site.

Irmo Mayor Bill Danielson welcomed the charter school to the town at Thursday’s press conference.

“We’re excited to have you in our community,” Danielson said. “It’s all about competition and educating the kids ... just don’t complain about Broad River Road. They’re going to widen it any day now, but that’s DOT.”

The addition of a satellite campus could enhance Gray’s athletic program, which has won 14 state championships since it opened in 2014. The War Eagles weren’t eligible for the postseason until 2016.

Gray Collegiate is in Class 4A for the first time this school year after competing in Class 2A since its inception. The enrollment boost from a satellite campus could push the War Eagles to 5A, which features the state’s biggest schools, by the time the next reclassification kicks in for the 2026-27 school year.

This year’s realignment included a multiplier for the first time and was done in part due to the athletic success of public charter schools like Gray and Oceanside Collegiate and private schools like Christ Church and St. Joseph’s. The out-of-zone multiplier took each student who lives outside of a school’s assigned attendance zone and counted them as three for total enrollment purposes.

The result inflated schools’ official enrollment figures and, in some cases, raised schools up one or multiple levels in classification for athletics.

According to the 45-day average daily membership (used for 2024-26 realignment) obtained by The State via a public records request, 400 of Gray’s 496 students in grades 9-11 come from outside its given attendance zone by the South Carolina High School League, which is Brookland-Cayce High School in Lexington 2. That’s the range the league uses to determine is multipliers. It’s unclear how many of those Gray students play sports.

Gray Collegiate athletic director Kevin Heise said Gray’s enrollment is currently 938 with an estimated 620-625 students in high school. The satellite campus is expected to house up to 600 students but only freshmen and sophomores will count toward the school’s realignment numbers.

Heise estimates there will be 100 to 200 high school students at the satellite campus and the number is likely to grow.

All athletic practices and events will remain at the West Columbia campus, but a shuttle will run between campuses every afternoon to take students to their practices. Parents will have to pick up their child up at the West Columbia campus.

In 2023, Gray opened an on-campus gymnasium and then an athletic complex to host football, baseball and softball games was opened last year. The school added two new sports this year: girls golf and wrestling.

“It comes with trepidation. It forces us into the 5A ranks on the Division II 5A if the multiplier stays the same at three,” said Heise, who also is the school’s soccer coach. “We are comfortable at 4A, 5A as long as teams will play us. We just want competition and we don’t want to have to go through weekly ‘Hey they aren’t going to play us’ and we got to find a replacement. We are ready to get past that.”

In 2023-24, teams in Gray’s region in 2A refused to play them in all region games. This year in the new 4A region, Lexington 2 schools Brookland-Cayce and Airport aren’t playing the War Eagles in sub-varsity games.

The addition to the satellite campus might come with some pushback from Class 5A neighbors Irmo and Dutch Fork athletic programs. Dutch Fork has been the state’s most successful public school football program over the past decade and Irmo football played for a state championship in football this year.

Both schools are successful in other sports other than football.

“I’m sure there will be some of that. School choice and parents decide where they put their kids and what not,” Heise said. “I wouldn’t be surprised if the state goes to open enrollment at some point. There is a demand and clamoring for it. … The landscape has changed and if they can put their kids in what is perceived as a better opportunity for their child it is hard to hold them back in doing so.”